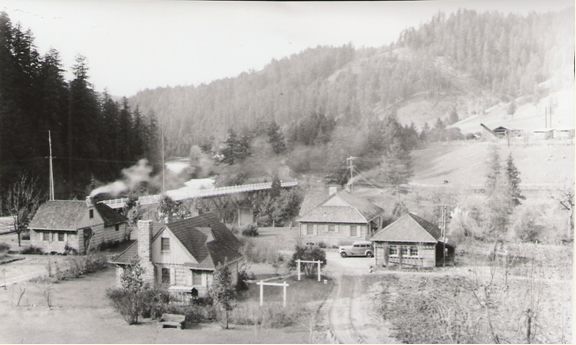

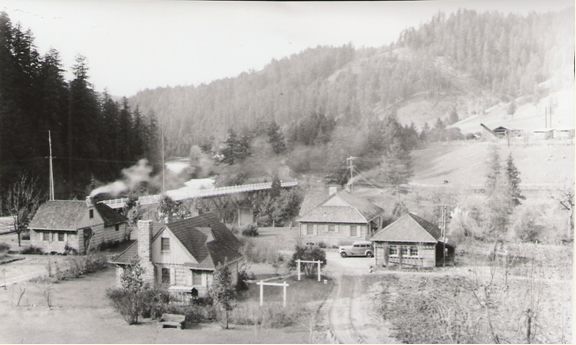

Tiller Ranger Station, 1941

The following column ran in The News-Review on August 20, 2021

On April 20, the Umpqua National Forest announced via press release that a feasibility study would be conducted to determine the future of the Tiller Ranger Station. The announcement was followed by a virtual “town hall” on July 21 detailing key considerations for the study and an in-person meeting on Aug. 3 that offered more time for questions.

As a long-time resident of Tiller, I was disappointed to hear about the proposed relocation — but not entirely surprised. The Tiller Elementary School and Tiller Market have both closed and the entire town has been sold to developers who appear to have zero interest in developing. As such, I was open to hearing an explanation about why such a move was being considered and how a new location might better serve the community.

The two meetings, however, left me with serious concerns about the decision-making process.

It was evident in the July 21 Zoom meeting that the idea of “public input” was a charade. The operating assumption seemed to be figuring out when and where the relocation should occur, not if.

The audience at the Aug. 3 meeting recognized this as well, and repeatedly pressed for answers about why the move was being considered in the first place. There appear to be three main considerations:

Facility maintenance

The Forest Service estimates that deferred maintenance costs for repairing buildings and associated infrastructure could be as high as $11 million. That’s clearly an enormous price tag — although one that reflects some questionable calculations.

During the Aug. 3 meeting, for example, Forest Supervisor Alice Carlton claimed that sewage from the water treatment plant could soon flow into the river and “threaten coho salmon.” This claim seems wildly implausible given the limited size of the treatment operation.

Carlton and Forest Engineer Steve Marchi both stated that relocating into a scaled-back facility would mean the district would no longer have to pay for maintenance of government housing. Unanswered, though, was the question of where the workforce would then live. The nine houses on the main compound and six apartment units on nearby Mill Hill are all currently full.

Telecommunications

The Tiller Ranger Station’s internet connection is currently provided by a fiber-optic cable that was installed many years ago, and the internet speed is surely suboptimal for a ranger station that needs to digitally communicate and collaborate with other offices.

Yet, it’s worth noting this problem is not unique to Tiller. The Toketee Ranger Station, for instance, also does not have broadband. In addition, many of the desk jobs that require all-day internet have already transitioned to Roseburg, and the fire fighters, biologists, and wilderness techs who comprise the Tiller workforce spend most of their time out in the field.

Tiller also does not have any cell phone service, which leaves those of us who live here at the mercy of landlines. It’s not clear how moving the ranger station would address the problem, as the forest itself would still be outside the range of mobile networks.

Recruitment & retention

This is one issue Mahnchi kept returning to: Even if you fix up the Tiller Ranger Station, how will you attract a workforce to come live here? He referred to the district’s long-time employees as “ticks” — people who had become embedded in the community and were willing to stay — and claimed that there were fewer and fewer ticks available.

I have no doubt that recruitment and retention are both challenges, but — as Mahnchi himself noted — all of the government housing at Tiller is currently full. Seasonal workers, at least, are very willing to spend their summers in Tiller. And full-time employees have historically lived outside of Tiller, whether in Days Creek, Shady Cove, or beyond.

Manchi noted that federal workers are attracted to places like the Deschutes National Forest (near Bend) and Mt. Hood National Forest (near Portland). This may be true, but relocating the ranger station from Tiller to Canyonville is unlikely to move the needle when competing for workers dead set on being near major metros.

Unanswered questions

I will concede that many of the suggestions for Tiller’s future coming from community members are colored by nostalgia for Tiller’s past — about the way things “used to be” when timber was being harvested, the school was a community hub, and cold beer was flowing at the local tavern.

This line of thinking can be counterproductive, as it suggests the only way to “fix” the situation is to return to a previous status quo — which, for reasons too numerous to detail here, seems unlikely.

But the case for relocating the Tiller Ranger Station seems equally detached from reality, especially given the necessity of keeping fire resources in proximity to the forest. It’s thus important that not only Tiller community members, but stakeholders from across the county weigh in on this decision-making process before it’s too late.

Pete Hunt is a long-time resident of Tiller and former employee of the Tiller Ranger District. His writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, The Diplomat, Willamette Week, and other outlets.